For many Americans, lakes and rivers provide a much-needed escape—a place to cool off on a hot day, relax with loved ones, or simply enjoy the beauty of nature. However, water quality remains a major public health concern across large portions of the United States. According to data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), over 70% of freshwater lakes, ponds, reservoirs, and wetlands (by acreage) and over 42% of creeks, rivers, and streams (by mileage) are considered too polluted for primary contact recreation such as swimming.

To help monitor and protect U.S. waterways from harmful contaminants, the Federal Water Pollution Control Act was significantly reorganized and expanded in 1972 to become known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). These amendments made it unlawful to discharge pollutants into most waters without a permit, empowered the EPA to implement pollution control programs, and funded the construction of sewage treatment plants.

While these actions are tangible progress towards protecting U.S. water quality, several challenges remain. One of the biggest hurdles faced today is nonpoint source pollution—contaminants that originate from many diffuse sources and collect in America’s waters—which is difficult to trace and therefore thinly regulated by the CWA. Major obstacles like nonpoint source pollution, particularly agricultural runoff, highlight the need for continued efforts to ensure clean water for all.

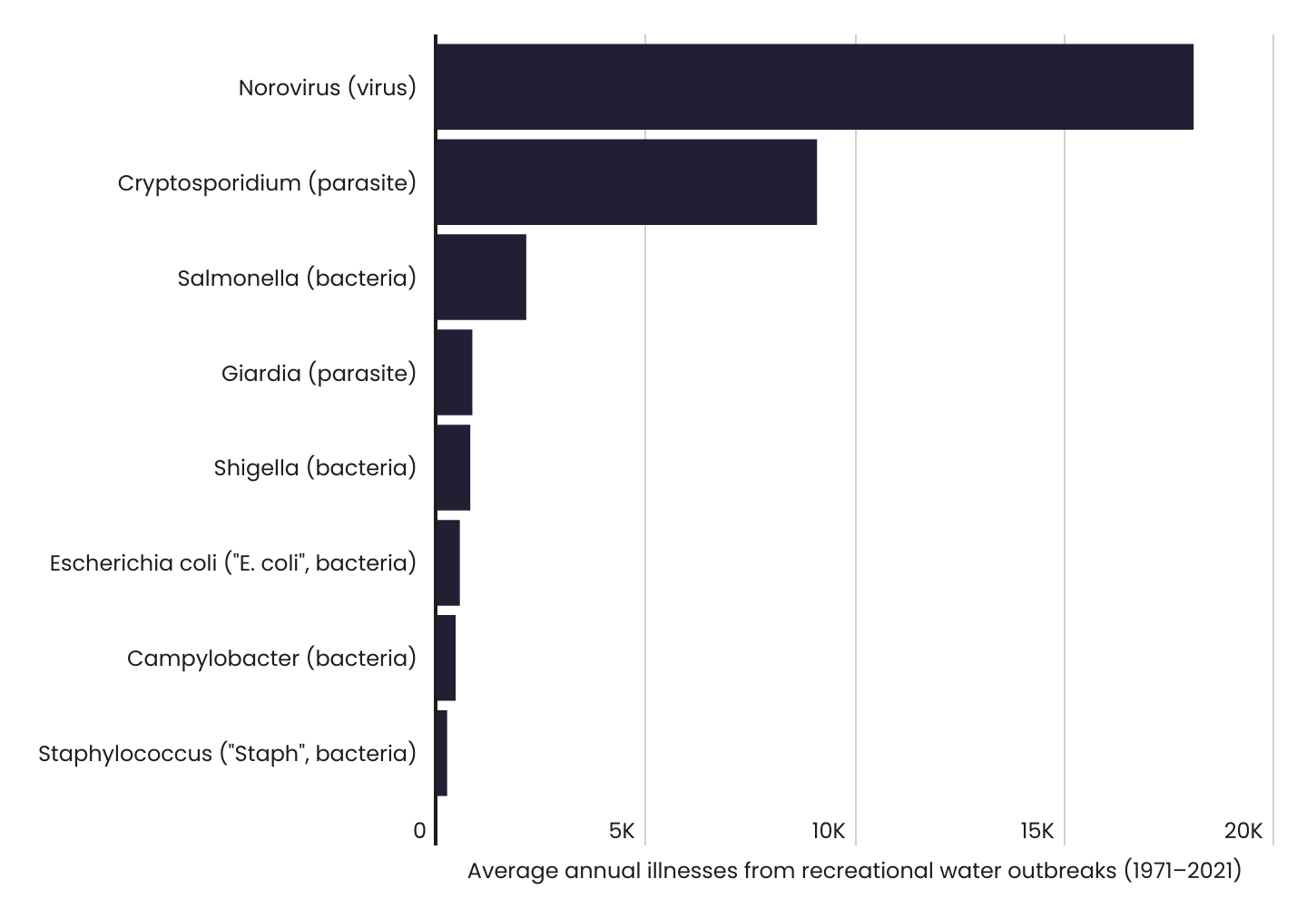

Top Causes of Recreational Waterborne Disease Outbreak

Norovirus accounts for the majority of recreational waterborne illness occurrences in the U.S.

Source: Captain Experiences analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data

On average, there are nearly 35,000 waterborne illness cases caused by recreational water use in the U.S. every year. Pathogens from sewage spills, animal waste, fecal incidents, water runoff after heavy rain, and naturally-occurring organisms can all contribute to water pollution, leading to health risks for swimmers ranging from gastrointestinal discomfort and skin rashes to more emergent health problems like respiratory complications, and even death.

Norovirus—a highly-contagious virus that causes vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain—is the most commonly acquired illness from recreational water disease outbreaks in untreated waters. With an average of over 18,000 cases reported annually from 1971 through 2021, it accounts for over 55% of diseases linked to primary contact water recreation—where the potential for ingestion of water is likely, such as swimming, diving, or surfing. A more dangerous cause of illness is Staphylococcus—a bacteria sometimes found in contaminated water. While it is responsible for an average of just 232 cases per year from water recreation, if left untreated, a “staph” infection can cause sepsis or can even be fatal.

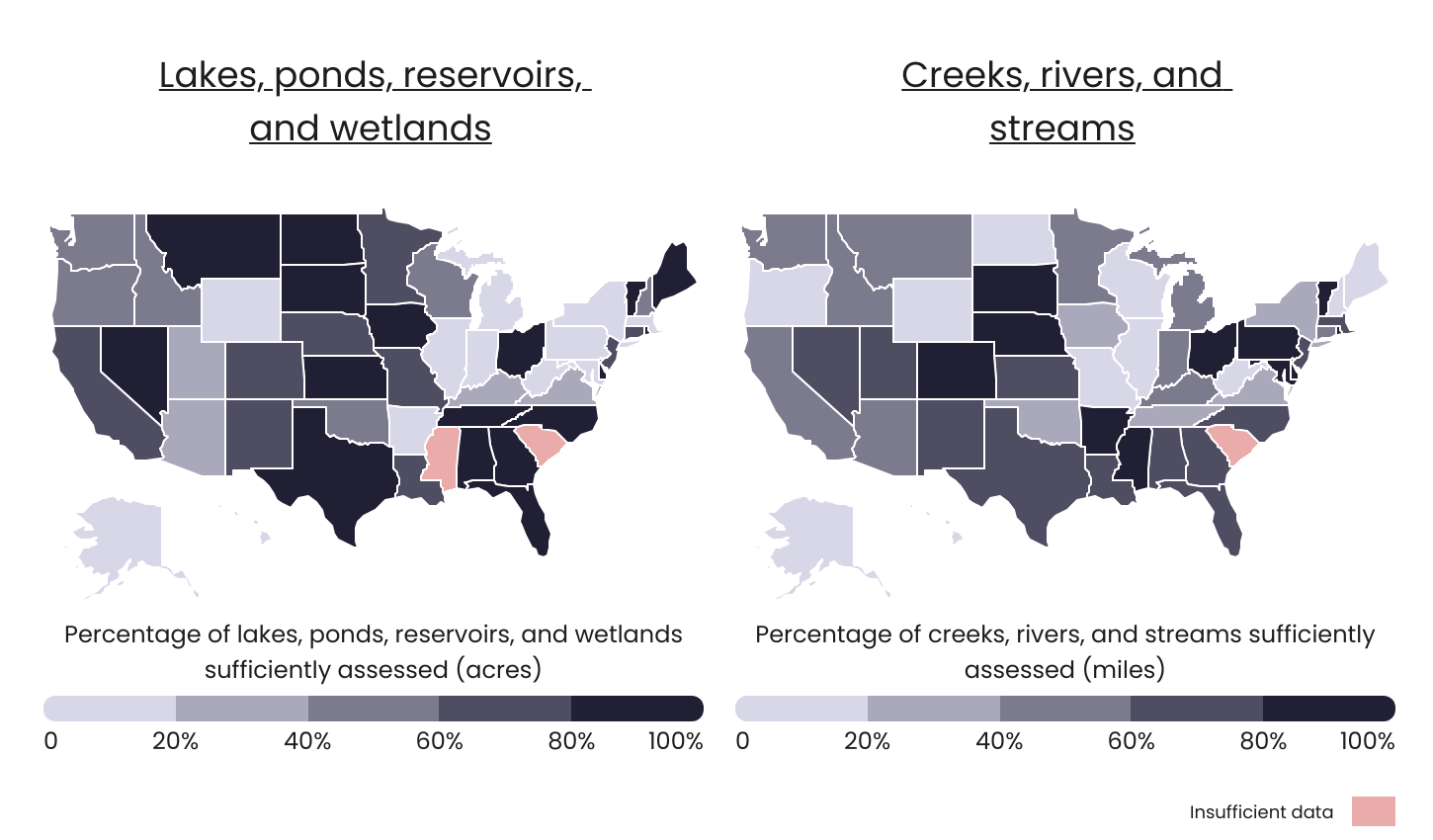

Recreational-Use Water Assessment Progress by State

Only 19 states have assessed a majority of their recreational-use lake and river waters for impairments

Source: Captain Experiences analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean Water Act data

Despite being established in 1972, the CWA has fallen short of its goal to make 100% of U.S. waters “fishable and swimmable” in large part due to inefficient and insufficient water quality monitoring. Just 19 states have recently assessed a majority of their recreational-use lakes and rivers for impairments, with Rhode Island being the only state to completely assess all of its recreational-use water bodies. Perhaps surprisingly, Wyoming, a state known for its natural beauty and outdoor recreation, has yet to sufficiently assess any of its several lakes and reservoirs designated for primary water contact use, and has evaluated just 5.7% of its creeks, rivers, and streams.

A major roadblock to water quality monitoring is the lack of enforcement by the EPA. Instead, the EPA relies heavily on state environmental agencies to regulate themselves, but without proper oversight and inadequate funding, some states are forced to make tough decisions such as only prioritizing perennial waterways or dedicating a disproportionate amount of resources on their most polluted water bodies. Lenient runoff pollution regulations, inefficient government enforcement of permit requirements, and weak management of interstate water pollution also contribute in creating a significant blind spot in water quality monitoring.

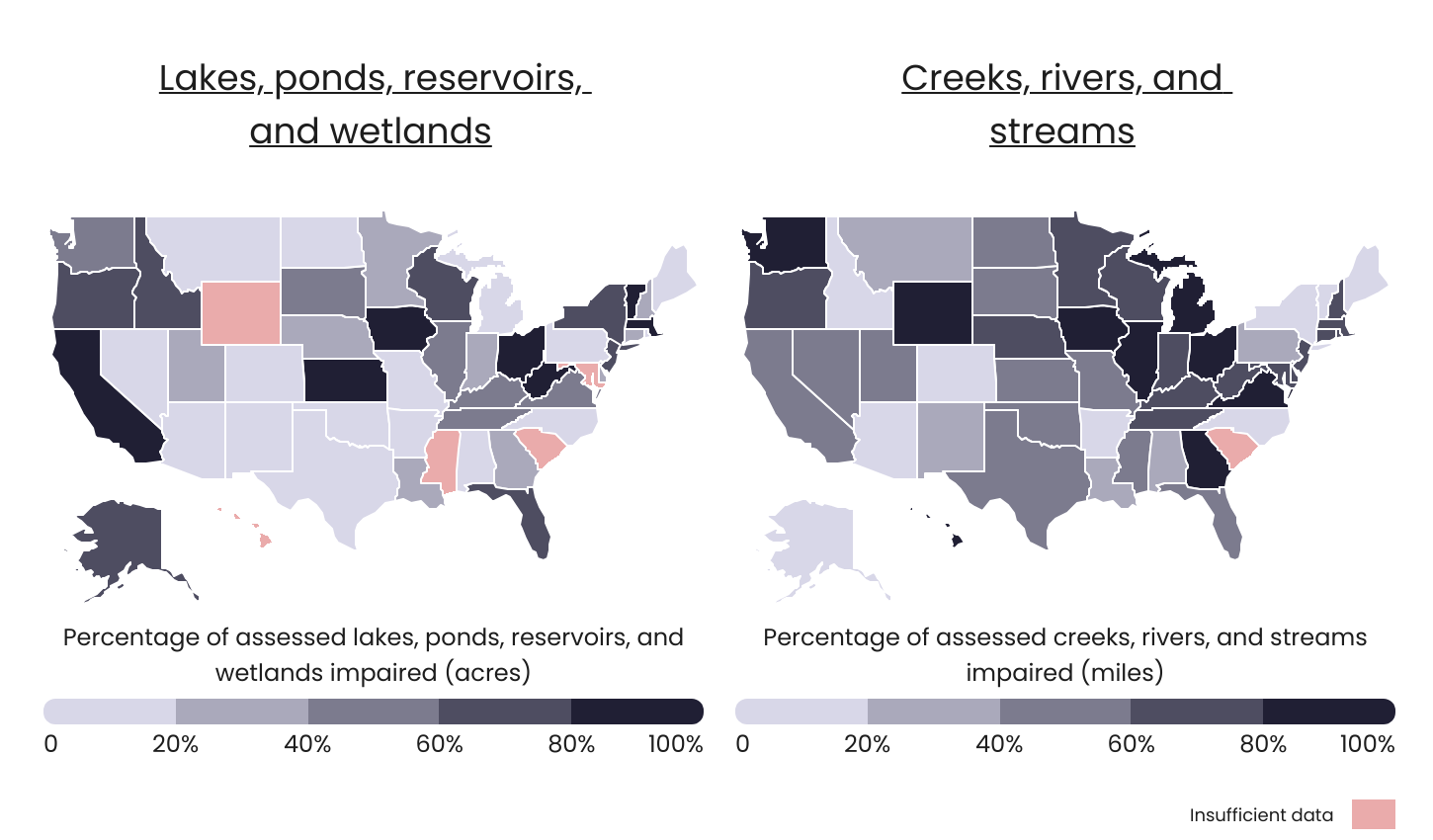

Geographical Differences in Impaired Recreational-Use Waters

Lake and river recreational-use water quality varies dramatically by state

Source: Captain Experiences analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean Water Act data

States define, designate, and prioritize water bodies differently, which makes comparison especially complicated when it comes to water quality progress. But overall, the majority of Americans believe the federal government is doing too little to protect water quality.

When it comes to lakes, reservoirs, and similar bodies of water, states in the Southwest tend to have the least contaminated waters. New Mexico (0.0%), Colorado (0.0%), and Texas (0.7%) all have less than 1% of recreational-use waters deemed impaired under the CWA, and all three states have assessed at least two-thirds of all of those waters that reside within their state borders. In contrast, West Virginia has the largest share of recreational lake acreage considered impaired with 91.6%, but only 15.2% of all lake waters have been assessed, leaving over 20,000 acres of lakes uncertain for swimming.

In many ways, rivers, creeks, and streams can be more difficult to assess for impairments because many are ephemeral, intermittent, or tidal. Nationally, by mileage, only 37.3% of these water bodies have been adequately assessed for primary water contact impairments. Colorado (3.0%), Arkansas (3.5%), and Vermont (3.8%) stand out as the only states to have less than 4% of rivers impaired and over 86% of all river mileage assessed. Conversely, Hawaii has only assessed 15.2% of its recreational water mileage, but the entirety of those 470 miles that were assessed were determined to be impaired for primary water contact recreation. This contamination has mostly been attributed to fertilizer runoff from golf courses, agricultural runoff, and fecal bacteria contamination from septic tanks.

The research was conducted by Captain Experiences—a fishing and hunting guide reservation platform—using the latest data available from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). For a complete breakdown of recreational-use water impairments across all 50 states, see States That You Should Think Twice About Swimming In on Captain Experiences.

Methodology

Photo Credit: Actium / Shutterstock

The data used in this analysis is from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean Water Act ATTAINS data. In order to determine the states with the worst water quality for swimming, researchers calculated the percentage of total acreage or mileage of assessed, untreated waters that were impaired for primary water contact. Impaired waters are bodies of water polluted by various sources such as industrial waste, sewage, or agricultural runoff, which makes them unsuitable for their designated uses. Under the mandate of the Clean Water Act, states are required to identify these polluted waters every two years and to take actions towards reducing this pollution. In some cases, broader recreational-use categories were used in states where primary water contact is not distinguished, and only waters designated with sufficient information were considered assessed. Untreated recreational-use waters, unlike chlorinated swimming pools, contain water that has not undergone a disinfection or treatment process to maintain good microbiological quality for recreation.

For clarity, acreage-based water bodies were grouped together, including: lakes, ponds, reservoirs, and wetlands, while mileage-based water bodies such as creeks, rivers, and streams were analyzed collectively. Further, the latest organizational submission data for each state was used, and other water bodies—such as oceans, Great Lakes, beaches, and bays—were excluded due to state-to-state data inconsistencies in categorization and reporting. For additional context, the percentage of primary-contact-use waters assessed, total assessed primary-contact-use waters impaired, total primary-contact-use waters assessed, and total primary-contact-use waters not assessed were calculated for both acreage- and mileage-based water bodies.

For complete results, see States That You Should Think Twice About Swimming In on Captain Experiences.